A little-known fact about Marie Laveau is that she and her domestic partner, Christophe Glapion, were slave owners. During the early antebellum period up until the Civil War, the illegal trafficking of slaves was rampant. The slave institution was undergoing changes that were influenced by a number of historical events, one of which was the Haitian revolution. As New Orleans was building its agriculture and business sectors with a proliferation of sugar and cotton plantations, there was a great demand for slave labor. However, the transatlantic slave trade ended in 1808, which ended the legal importation of enslaved people. Despite this new law, New Orleans remained a major site for human trafficking, which actually increased. Some of this activity involved the ongoing importation of enslaved human beings from the Caribbean, but Louisianans largely avoided importing slaves from Haiti specifically due to fear of their revolutionary spirit. They much preferred to receive enslaved people directly from Africa, as it was believed these human commodities wouldn’t be under the influence of such radical ideas as overthrowing their white government. The slave market was further fueled from the resale of enslaved Africans from the upper south (North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, Kentucky, and West Virginia) to the lower Mississippi Valley, which extends from Cape Girardeau, Missouri, to the Gulf of Mexico.

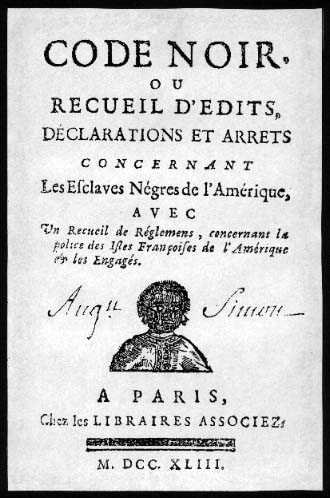

Marie Laveau bore witness to an incredibly difficult time in history. Though she was born a free woman of color, her role as a slave owner meant she was subject to the restrictions of the Louisiana Black Codes. Though we have no documented records of how she treated her slaves, my guess is that if she were a tyrant like the infamous Delphine LaLaurie, for example, it would have become part of the Laveau legend. Thus, the absence of horror stories in this regard seems to be a good thing.

Marie Laveau bore witness to an incredibly difficult time in history. Though she was born a free woman of color, her role as a slave owner meant she was subject to the restrictions of the Louisiana Black Codes. Though we have no documented records of how she treated her slaves, my guess is that if she were a tyrant like the infamous Delphine LaLaurie, for example, it would have become part of the Laveau legend. Thus, the absence of horror stories in this regard seems to be a good thing.

The Louisiana Black Code or Code Noir was enacted in 1724 during the administration of Governor Bienville and was based on earlier codes developed in the French Caribbean colonies. The codes were designed to limit the freedom of African Americans in the colony, to prevent desertion, and ensure the availability of a cheap labor force following the abolishment of slavery during the Civil War. Slave owners were mandated to baptize their slaves in the Catholic faith and to give them Sundays off for worship. Slaves were allowed to marry, separation of families was not permitted, and slave owners were not allowed to severely beat or murder the enslaved. While the French laws provided greater rights to slaves than their British and Dutch counterparts, Louisiana’s law differed in several negative ways. They restricted the movement of people of African descent and stipulated that the status of people with darker skin was always lower than those with lighter complexions. Additionally, it intentionally thwarted contact between racial groups. There were also articles within the Code Noir that were intended to ensure the safety and well-being of slaves as merchandise so that they could be productive workers. While the Code Noir allowed slaves to report to authorities if they were not given these basic provisions, reports were rare and instead the enslaved often resorted to running away. The runaway slaves were referred to as Maroons.

In 1811, Marie Laveau was about ten years old and Louisiana was still the Territory of Orleans. The largest slave revolt in American history, referred to as the German Coast Uprising, occurred about thirty miles outside of the city that year. Enslaved men rebelled against the harsh conditions of the sugar plantations, even though they should have been protected by the Louisiana Black Codes. Between two hundred and five hundred enslaved men armed with mostly hand tools participated in the march from the sugar plantations on the German Coast toward New Orleans (Genovese 1976). Along the way, they burned five plantation houses, several sugar houses and crops. The rebels ended up only killing two white men. Confrontations with White militias and soldiers hunting down the slaves, however, ended in the execution and decapitation of over 100 of the rebels, whose heads they publicly displayed in an effort to intimidate and discourage further revolts (Rasmussen 2011).

While President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation had theoretically abolished slavery in 1863, it was officially abolished by the state constitution of 1864, during the American Civil War. Marie Laveau was born a free woman of color, but for most of her life slavery was alive and well. It was commonplace for free people of color to own slaves, and almost all New Orleanians of means did so. Some bought slaves and allowed them to work for hire elsewhere while collecting a percentage of their wages, while others were purchased as household servants.

The issue of motivation behind Marie Laveau’s status as a slave owner is unknown. It is highly likely that experiencing the events of her childhood as a possible witness to the uprising impacted her into adulthood. Just as those of us who lived during the attacks of September 11 will always be affected by them, whether we lived in New York City or on the Gulf Coast, Marie had to have been affected by the largest slave revolt in American history. There is no evidence Marie was involved in the slave trade prior to her partnership with Christophe Glapion, but there is archival evidence that he was involved in the buying and selling of slaves prior to being with Marie (Long 2006). This is not surprising, as he was French and the French embraced slave ownership as part of their culture. Since 1706, chattel slavery had been perpetrated against Native populations in Louisiana until 1768 when, under Spanish rule, the enslavement of indigenous peoples was banned. This ban did not include Africans or people of African descent, however. Spanish rule did eventually introduce coartación, a new law that allowed slaves to buy their freedom and freedom for other slaves. It was under this law that Marie’s grandmother Catherine was able to purchase her freedom in 1795.

Once Marie and Christophe became a couple, they bought and sold eight slaves (Long 2006). Like most other slave owners of their time, they bought slaves, kept them for a little while, and then sold them, often at a profit. There are no reports or articles available to tell us how they treated their slaves. However, the idea has been put forth that the Laveau-Glapion home served as a Southern depot for the Underground Railroad and that they helped to free slaves. Marie is known through oral history to have provided slaves with charms to protect them on their journeys to freedom.

Marie and Christophe continued buying and selling slaves until 1854, when Christophe sold his final enslaved woman. If indeed Marie was involved in assisting slaves in their quest for freedom, it would make sense that she would not compel Christophe to stop buying and selling slaves—because that would be a red flag to outsiders, as it was something he was known for doing prior to being with her. Why she participated as well during their time together is a more difficult question to answer. Although it could be that finances would not permit it, it is noteworthy that Marie did not participate in the slave trade after Christophe’s final sale in 1854, or after his death in 1855.

Once Marie and Christophe became a couple, they bought and sold eight slaves (Long 2006). Like most other slave owners of their time, they bought slaves, kept them for a little while, and then sold them, often at a profit. There are no reports or articles available to tell us how they treated their slaves. However, the idea has been put forth that the Laveau-Glapion home served as a Southern depot for the Underground Railroad and that they helped to free slaves. Marie is known through oral history to have provided slaves with charms to protect them on their journeys to freedom.

Marie and Christophe continued buying and selling slaves until 1854, when Christophe sold his final enslaved woman. If indeed Marie was involved in assisting slaves in their quest for freedom, it would make sense that she would not compel Christophe to stop buying and selling slaves—because that would be a red flag to outsiders, as it was something he was known for doing prior to being with her. Why she participated as well during their time together is a more difficult question to answer. Although it could be that finances would not permit it, it is noteworthy that Marie did not participate in the slave trade after Christophe’s final sale in 1854, or after his death in 1855.

Voudou is a signifying science—signs, symbols, codes, and signifiers are embedded in the tradition. Support for Marie Laveau as an abolitionist or even a station master for the Underground Railroad and the Laveau- Glapion home as a safe house comes from one very small, yet significant clue recalled by a man named Charles Raphael, born in 1868. He describes the altar in her front room, which had items on it like “good luck charms, money-making charms, and husband-holding charms.” He adds, “On this altar she had a statue of St. Peter and St. Marron, a colored saint.” Now, all safe houses in the Underground Railroad network held signifiers to indicate it was a safe space for fugitive slaves such as passwords, call-and-response songs, coded knocks on doors, and quilts bearing special designs. These types of signals would have been easy to mask the already foreign Voudou activity going on at the home. But it is the presence of a statue of St. Maroon that screams the loudest, because St. Maroon is the patron saint of runaway slaves.

To put it into a modern context, if we look at how various Latin American folk saints are found among drug dealers and smugglers today, we can see some parallels. For example, some drug dealers and users alike believe that having a statue of Jesús Malverde nearby renders their drug stash invisible. Law enforcement agrees that a “Malverde statue in the home of an already suspected drug dealer is considered a red flag to officers, indicating illegal substances may be on the premises” (Davis 2007). Likewise, the presence of a statue of St. Maroon in the home would signify someone sympathetic to the abolitionist movement.

In New Orleans Voudou and folk Catholicism, it is common practice to pair up saints according to purpose. For example, St. Expedite, the patron saint of expediency, may be paired with St. Jude, the patron saint of hopeless causes, to ensure petitions to St. Jude are answered with haste. St. Expedite is “sent in” with St. Jude to make the case with Bon Dieu (God) on behalf of the petitioner. This ritual dynamic is tantamount to a spiritual buddy system whereby the saints benefit from each others’ special talents while the petitioner benefits from their combined efforts. Petitioning St. Jude alone does not guarantee expediency; in fact, he can be slow to work at times. So, if a petitioner needs a seemingly hopeless case addressed quickly, St. Expedite can make it happen. Now, if we consider the two saints on Marie Laveau’s altar in the context of Voudou and folk Catholicism, we can parse out what is going on as it relates to assisting runaway slaves. First, we have St. Peter, who is syncretized with Papa Legba. St. Peter holds the keys to the kingdom of heaven, while Papa Legba holds the keys to the spirit world. These two energies are tapped into in Voudou when there are obstacles that are in need of removal, roads that need to be open, and secrets that need to be kept under lock and key. The keys also signify the ability to unlock the chains of slavery. Thus, St. Peter holds the keys to what fugitives referred to as “heaven” (which referred to freedom in Canada), and St. Maroon provides protection on the freedom train.

To put it into a modern context, if we look at how various Latin American folk saints are found among drug dealers and smugglers today, we can see some parallels. For example, some drug dealers and users alike believe that having a statue of Jesús Malverde nearby renders their drug stash invisible. Law enforcement agrees that a “Malverde statue in the home of an already suspected drug dealer is considered a red flag to officers, indicating illegal substances may be on the premises” (Davis 2007). Likewise, the presence of a statue of St. Maroon in the home would signify someone sympathetic to the abolitionist movement.

In New Orleans Voudou and folk Catholicism, it is common practice to pair up saints according to purpose. For example, St. Expedite, the patron saint of expediency, may be paired with St. Jude, the patron saint of hopeless causes, to ensure petitions to St. Jude are answered with haste. St. Expedite is “sent in” with St. Jude to make the case with Bon Dieu (God) on behalf of the petitioner. This ritual dynamic is tantamount to a spiritual buddy system whereby the saints benefit from each others’ special talents while the petitioner benefits from their combined efforts. Petitioning St. Jude alone does not guarantee expediency; in fact, he can be slow to work at times. So, if a petitioner needs a seemingly hopeless case addressed quickly, St. Expedite can make it happen. Now, if we consider the two saints on Marie Laveau’s altar in the context of Voudou and folk Catholicism, we can parse out what is going on as it relates to assisting runaway slaves. First, we have St. Peter, who is syncretized with Papa Legba. St. Peter holds the keys to the kingdom of heaven, while Papa Legba holds the keys to the spirit world. These two energies are tapped into in Voudou when there are obstacles that are in need of removal, roads that need to be open, and secrets that need to be kept under lock and key. The keys also signify the ability to unlock the chains of slavery. Thus, St. Peter holds the keys to what fugitives referred to as “heaven” (which referred to freedom in Canada), and St. Maroon provides protection on the freedom train.

How to cite this page

Please take a moment to cite this page if you use the information. I've done the heavy lifting for you; all you have to do is copy and paste the reference.

APA 6th

Alvarado, D. (2019). The Slave Owner. Retrieved from https://www.marie-laveaux.com/slave-owner-1.html.

Alvarado, D. (2019). The Slave Owner. Retrieved from https://www.marie-laveaux.com/slave-owner-1.html.

Chicago 16th

Alvarado, Denise. “The Slave Owner,” 2019. https://www.marie-laveaux.com/slave-owner-1.html.

Alvarado, Denise. “The Slave Owner,” 2019. https://www.marie-laveaux.com/slave-owner-1.html.

MLA 8th

Alvarado, Denise. The Slave Owner. 2019, https://www.marie-laveaux.com/slave-owner-1.html.

Alvarado, Denise. The Slave Owner. 2019, https://www.marie-laveaux.com/slave-owner-1.html.

The Magic of Marie Laveau

Preorder the book scheduled for release February 1, 2020.

|